The monument to the 2nd Maryland Infantry Regiment on Lower Culp’s Hill/Spangler’s Hill. The Baltimore Cross is on each of the four faces of the capstone as most of the men in the regiment were recruited from Baltimore. The Maryland State Seal is the large bas relief carving on the front. This image was taken facing east at approximately 7:45 PM on Sunday July 31, 2016.

This aerial view shows the area of Lower Culp’s Hill/Spangler’s Hill – the red star marks the location of the 2nd Maryland Infantry monument. This image is courtesy of Google Maps.

The monument is notable for being the first Confederate monument at Gettysburg. It was dedicated on November 19, 1886. It is also notable for the change chiseled into the monument above “2nd MD. Infantry CSA,” reminding visitors that the regiment was composed of many men and officers from the 1st Maryland Infantry Regiment. The 1st Maryland was disbanded after its initial 12-month duty, and when the new regiment was formed it was named the 1st Maryland Battalion. The unit was not known as the 2nd Maryland Infantry until January of 1864 and would have been referred to as the 1st Maryland Battalion during the Battle of Gettysburg. This image was taken facing east at approximately 7:45 PM on Sunday July 31, 2016.

This panorama shows you the Union earthworks that run along the front (west side) of the monument – the 2nd Maryland Infantry attacked these works and held them on the night of July 2nd and into the morning of July 3rd. These were reconstructed by the Civilian Conservation Corps in the 1930s and are not the original works. The right flank marker to the 2nd Maryland Infantry is located behind the earthworks in the right of frame (LBG Charlie Fennell describes the position of the 2nd Maryland behind the works). The primary monument to the 29th Pennsylvania Infantry is in the back left of frame. It is currently missing the bronze eagle which sits atop it. This eagle is being used to mold the eagles in the reconstruction of the Hancock Avenue gate. This panoramic image taken facing southwest to west at approximately 7:45 PM on Sunday July 31, 2016.

The 2nd Maryland monument is also notable for a supposed burial trench in the woods behind it. Soldiers in 1863 would have had a far clearer line of the sight through the woods than we did Sunday evening. This image was taken facing east at approximately 7:45 PM on Sunday July 31, 2016.

Walk to the left of the monument towards the large boulder in the first photo in this post… This image was taken facing northeast at approximately 7:45 PM on Sunday July 31, 2016.

…and you’ll see a path into the woods. This image was taken facing east at approximately 7:45 PM on Sunday July 31, 2016.

This William H. Tipton stereo shows one of the burial trenches on Culp’s Hill that at one time contained Confederate dead. This image was taken circa 1880.

Dead Confederate soldiers were the last to be removed from the battlefield, with the major effort to send them south taking place in the 1870s. The supposed burial trench is marked with Confederate flags behind the rocks here. We refer to it as a “supposed” burial trench because it doesn’t resemble other trenches on Culp’s Hill and we have not seen evidencing suggesting it is one. This image was taken facing east at approximately 7:45 PM on Sunday July 31, 2016.

The burial of the dead on Culp’s Hill was the stuff of nightmares. Major Philo Buckingham, from the 20th Connecticut Infantry, who was then working on Brigadier General Alpheus S. Williams’ staff during the battle, said that “some [men were] sitting up against trees or rocks stark dead with their eyes wide open staring at you as if they were still alive – others with their heads blown off with shell or round shot, others shot through the head with musket bullets. Some struck by a shell in the breast or abdomen and blown almost to pieces, others with their hands up as if to fend off the bullets we fired upon them, others laying against a stump or a stone with a testament in their hand or a likeness of a friend.” This image was taken facing west at approximately 7:45 PM on Sunday July 31, 2016.

By July 4th and 5th the bodies were swollen and blackened. Union troops were ordered to gather fallen soldiers from the rocks and logs strewn along the muddy hill. While Union dead usually received single marked graves, the Confederates were piled into shallow mass graves near where they fell. Gettysburg civilian Clifton Johnson described it: “They were burying the dead there in long narrow ditches about two feet deep. They would lay in a man at the end of the trench and put in the next man with the upper half of his body on the first man’s legs and so on. They got them in as thick as they could and only covered them enough to prevent their breeding disease.” This image was taken facing southwest at approximately 7:45 PM on Sunday July 31, 2016.

This section of the S.G. Elliott burial map shows the highlighted area of the 2nd Maryland Infantry monument and the supposed trenches behind it. The single dashes are Confederate soldiers and the crossed lines are Union soldiers. The Elliott Map should be approached with skepticism – it’s unclear how many of the gravesites Elliot verified in person versus what was reported to him by property owners and individuals like Dr. John W.C. O’Neal. This map was published in 1864.

This spot is fairly well-known as a gravesite and has been marked in various ways over the years (we recently remember a series of four logs surrounding the depression). The Confederate flags were not placed by the National Park Service. This image was taken facing southwest at approximately 7:45 PM on Sunday July 31, 2016.

Nine years had passed since the battle when Dr. Rufus Weaver (son of Samuel Weaver) was contracted by southern Ladies Memorial Associations (LMA’s) to complete removal of Confederate dead from the battlefield. Many of the graves were no longer marked in the early 1870s and some southern states could not pay Weaver the money necessary to remove the bodies from the field. Weaver’s main cost was shipping the bodies south, but he also had to negotiate and pay the farmers who owned the land fees to remove the bodies. The number of dead reported on the battlefield and the number of soldiers buried does not match up (half a dozen Confederates were mistakenly buried in the Soldiers National Cemetery). It is likely that hundreds of bodies remain on the battlefield. We are standing in the highlighted section of the Elliott map, on the east side of Lower Culp’s Hill. The 2nd Maryland would have been attacking towards the rock in the background on the evening of July 2nd, 1863. This image was taken facing west at approximately 7:45 PM on Sunday July 31, 2016.

A marker placed in honor of Dr. Rufus Weaver in Hollywood Cemetery. This image was taken in July of 2016 by Tracey Bear.

We’ll walk down Slocum Avenue to check out the other Confederate marker to the 2nd Maryland – the monument to the 111th Pennsylvania Infantry is closest to the camera. This image was taken facing northwest at approximately 7:45 PM on Sunday July 31, 2016.

Find the green mini-van in the left of frame. The 2nd Maryland Infantry monument is barely visible behind it. Around 10:30 AM on July 3rd, Confederates attacked from left to right down the hill towards the Union position in Pardee Field. The tiny marker near the woods in the far right of frame is the advance marker to the 2nd Maryland Infantry. This image was taken facing southeast at approximately 7:45 PM on Sunday July 31, 2016.

For more on this charge, see Licensed Battlefield Guide Charlie Fennell’s exceptional series on Culp’s Hill. The monument with the star in the left-background is to the 147th Pennsylvania Infantry – the monument to the right of the tree is to the 5th Ohio Infantry. This image was taken facing southwest at approximately 7:45 PM on Sunday July 31, 2016.

A regimental advance marker with a nearby monument is rare for Confederates at Gettysburg. But not only was the 2nd Maryland Infantry the first Confederate monument on the field, it’s also featured in a painting on a Culp’s Hill wayside. You’ll also notice that the advance marker refers to the regiment as the “1st MD Battalion.” This image was taken facing southwest at approximately 7:45 PM on Sunday July 31, 2016.

We’ve now moved to the observation tower on Culp’s Hill. This image was taken facing southwest at approximately 7:45 PM on Sunday July 31, 2016.

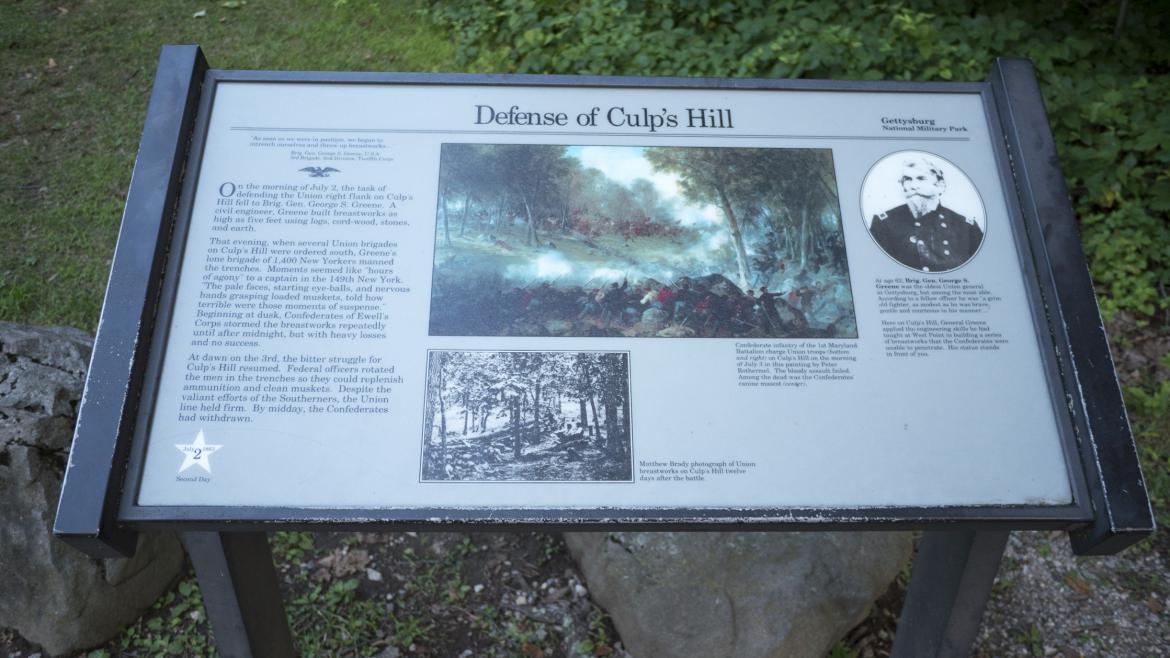

The wayside next to the statue of Brigadier General George S. Greene has the painting we’re looking for. This image was taken facing east at approximately 7:45 PM on Sunday July 31, 2016.

The painting, “Repulse of General Johnson’s Division by General Geary’s White Star Division, July 3,” was painted circa 1871-1872. This is the same period of time when efforts to bury the remaining Confederate dead on the battlefield began. This image was taken facing east at approximately 7:45 PM on Sunday July 31, 2016.

The caption on the wayside mentions that “Among the dead was the Confederates’ canine mascot.” This image was taken facing east at approximately 7:45 PM on Sunday July 31, 2016.

This Peter Rothermel painting hangs in the State Museum of Pennsylvania in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. This image was taken at approximately 12:15 PM on Friday March 25, 2016.

The 2nd Maryland Infantry’s “canine mascot” can be seen in the right-center of the painting. This image was taken at approximately 12:15 PM on Friday March 25, 2016.

The 200 yard charge down the northwest side of Culp’s Hill by Brigadier General George Steuart’s Maryland, Virginia, and North Carolina troops was unsuccessful. The dog was “perfectly riddled” by bullets and Union Brigadier General Thomas Kane was said to have ordered a “proper burial.” We can only wonder if Kane thought that he was supervising a “proper burial” of the Confederate humans in mass graves at Culp’s Hill. This image was taken at approximately 12:15 PM on Friday March 25, 2016.